This column, provided here to illustrate Mr. Tarapore's sharp focus on the common person and his depth of understanding of the core issues at hand, was written ahead of the monetary policy announcement of November 2011. It was released then as part of Mr. Tarapore's multi language syndicate service.

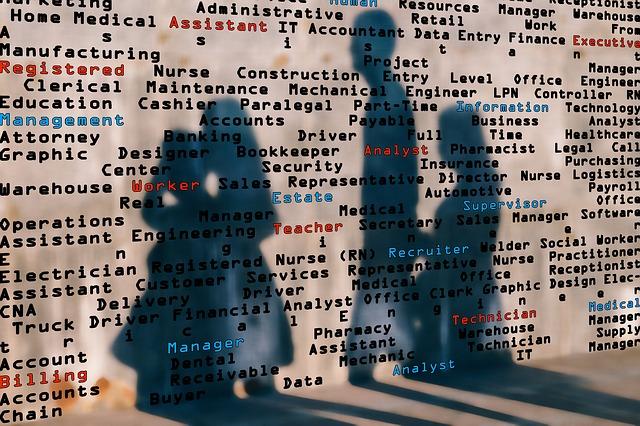

A key objective of macroeconomic policy is to generate 100 million new jobs over the next 10 years. While this is a laudable objective, attention needs to be focussed on some basic policies which militate against a rapid increase in employment.

In India, capital is scarce yet it is priced in at a very low level in terms of real rates of interest i.e. nominal interest rates adjusted for inflation. It is no wonder that policies encourage capital intensive development. It is argued that high real rates of interest hinder growth. If an economy is growing, at say 8 per cent per annum, a real rate of interest above 8 per cent would dampen growth. There is a strong view that savers have nowhere to go and that they would part with their savings at low nominal rates of interest.

While labour is in abundant supply, there is a paradox in that while overall wages are low, there are islands of high wages in select sectors. These distortions result in greater inefficiency in the system.

It is important to understand the relationship between the pattern of investment, employment and inequalities in incomes. If, for instance, there is large investment in automobiles, air conditioners, washing machines and other fancy goods, income will flow to the relatively high income groups which can afford to buy these goods. Such a pattern of investment would generate very little employment. With the advent of the Second Five Year Plan (1956-61) there was a clear tilt towards heavy industry which, in its nature, was capital intensive and generated relatively little employment.

If there is large investment in automobiles, air conditioners, washing machines and other fancy goods, income will flow to the relatively high income groups which can afford to buy these goods. Such a pattern of investment would generate very little employment.

In the 1950s, a minority of economists led by C.N.Vakil and P.R. Brahmananda argued that if investment was directed towards production of basic food grains and coarse cloth, income distribution would tilt towards the lower income groups.

It is often argued that growth is of paramount importance and as only growth can provide increased employment and uplift the lowest income strata, we should accept the fall out of rapid growth in terms of increased inequalities of income and inflation. It is well known that inflation hurts the weakest segments the most and hence if the choice is between growth and inflation it is preferable to have low growth with low inflation rather than high growth with high inflation. It is persuasively argued that the focus should be on the lowest income strata and if real incomes in this segment increase we should not be too concerned if there is increased inequality.

It bears emphasising that such an approach is hazardous as social tensions can boil over. There is a powerful “demonstration effect” of the lower income groups wanting to emulate the higher income groups particularly if the rich indulge in blatant conspicuous consumption, as indeed they have done in the past 20 years. With the unemployment lines increasing rapidly, the situation can become dangerous and there could well be a major social upheaval.

It is, therefore, imperative that increased employment should be at the top of the policy agenda and attention should focussed on how to bring about a quantum jump in employment.

There has to be an attitudinal change. We need not only barefoot doctors, but barefoot educators, barefoot bankers and barefoot administrators who would be exclusively entrusted with the task of increasing the envelope of employment. The task of generating 100 million jobs in 10 years is indeed daunting and the government should not hesitate to step up its employment generation schemes.

Quite often, the relatively high birth rate in India – the highest among the BRICS countries- is celebrated as a virtue under the misguided concept of a demographic dividend under which the proportion of the population which could be employed, i.e. between the ages of 18-60 would increase. It is argued that this will provide a large market for consumption of goods and services and there would be a virtuous circle of higher incomes and higher employment. If the country cannot provide adequate employment opportunities for the existing work force, it is stultifying to make a virtue out of population growth. Lowering population growth is easier said than done. It is only by providing effective universal health care and educational facilities that the population growth rate would come down and moderate the demand for employment.

Much as it is claimed that micro and small enterprises ( MSEs) have been provided with adequate incentives it is felt that while this sector provides the maximum employment it does not contribute sufficiently to increased productivity. In contrast, it is argued that large industry contributes the most to productivity. If increased employment is the over-riding objective, the whole system of incentives should be oriented towards increased employment.

It is often claimed that the commercial sector is the locomotive of growth of the economy and there is a tendency to denigrate the employment generation schemes of the government like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). It is claimed that while such schemes are employment intensive, they generate a shortage of labour in the industrial sector and thereby contributes to inflation. There are flippant views that these government schemes generate “unproductive employment” of digging holes and filling them up. It is, therefore, argued that schemes like the MGNREGS should be tweaked. This is a grossly unfair and biased assessment of schemes which have contributed to generating employment while adding to the country’s assets.

While “full” employment is a mirage, the objective should be to attain “fuller” employment’ i.e. a level of employment significantly higher than prevailing at present. It is also necessary to have a reasonably authentic assessment of the extent of unemployment and “disguised/under” employment.

There has to be an attitudinal change. We need not only barefoot doctors, but barefoot educators, barefoot bankers and barefoot administrators who would be exclusively entrusted with the task of increasing the envelope of employment. The task of generating 100 million jobs in 10 years is indeed daunting and the government should not hesitate to step up its employment generation schemes.