By Errol D’Souza and Astha Agarwalla

The COVID-19 induced lockdown has resulted in lost jobs and the closure of small and informal businesses everywhere. Entrepreneurs are facing cash flow issues and workers who have casual and informal employment are undergoing liquidity stress causing them to migrate back to their families.

While small and medium enterprises that constitute a part of the informal sector are a characteristic of fast-growing economies, it is a mistake to think that they are an important engine of economic growth just because they happen to dominate the economic landscape. Small firms do not offer stable employment and non-wage benefits. The empirical literature also does not support the notion that small firms offer a greater quantity of employment. Much of the focus in the policy circles has been on costs imposed by enforcement of labour laws regarding layoffs and retrenchment (the Industrial Disputes Act Chapter VB particularly) as a cause of and motivation for informality and the growth in casual employment. What has not been emphasised enough is how financial constraints and State regulations and laws, specifically those related to taxation promote informality and poor job growth.

While small and medium enterprises that constitute a part of the informal sector are a characteristic of fast-growing economies, it is a mistake to think that they are an important engine of economic growth just because they happen to dominate the economic landscape. Small firms do not offer stable employment and non-wage benefits.

Informality is a choice in relation to regulation by the State and financial development affects the decision to operate formally. Firms require external funds to grow which they obtain from financial intermediaries (FIs). In turn they must reveal details about their assets which serve as a signal of indemnity and allow FIs to disburse loans at rates that reflect the appropriability of the assets as collateral. Once a firm accesses the financial sector it leaves a paper trail that facilitates tax enforcement. Fiscal authorities are able to check information about transactions by a firm and the efficacy of taxation and its enforcement is improved if firms source finance and settle dues through the formal financial system. Transactions that are inherently informal and settled in cash are difficult to monitor and tax.

Many entrepreneurs are engaged in activities where social value is destroyed. There is value in upgrading organisations so that they do not provide low pay, hazardous jobs, or excessive hours of work.

External finance is valuable for increasing the productivity of operations. Its downside is that it exposes the establishment’s scale of operations and it then becomes liable to taxation. Firms will use the formal financial system only if it makes possible considerable value addition that exceeds the costs of accessing the FIs and the losses from being part of the tax net. Costs of accessing FIs include the time and money costs of acquiring financial literacy or relying on intermediaries. For a FI, institutions of governance that enable enforcement of loan contracts and recovery of dues when a borrower reneges are important determinants of funding the creditworthy. Thus, informality in terms of its characteristics (small size, nature of employment contracts and benefits provided) is a result of choices made by firms and FIs to institutions of governance.

Technological change which is the prime factor in growth in the advanced world takes place through the combined effort of independent and small inventors and large innovative firms that organize R&D. Small firms are able to promote innovation due to structural flexibility and their adaptability to individual needs and market conditions. Such firms need to be differentiated from those entrepreneurially eking out a living in small and medium enterprises through informal self-employment (the dominant form of employment) – they are there by necessity due to limited number of wage-paying jobs. In an advanced economy by contrast becoming an entrepreneur is a choice made to gain the returns available from a perceived opportunity. Such entrepreneurs transform business and provide valuable job creation ― employment being a derived demand dependent on the value they obtain from the goods they supply in the market. Healthy regulation promotes the entry and maturity of such entrepreneurial firms whilst protecting their customers and workers from unscrupulous and exploitative actions.

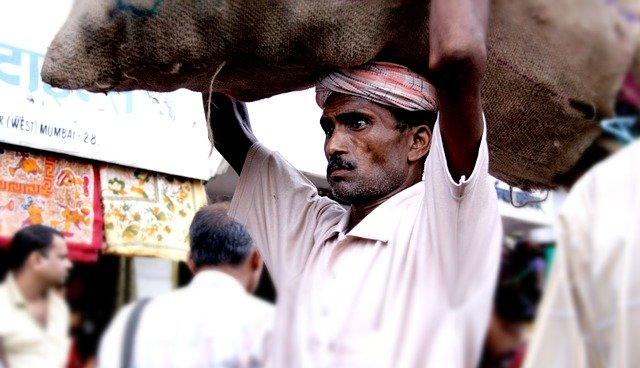

It takes no less than an economy-wide crisis to bring out the social and economic costs of informality and the importance of formalisation. The scenes of migrant workers walking home on foot soon after the lockdown order is an indication that informality is double-edged.

Many entrepreneurs are engaged in activities where social value is destroyed. There is value in upgrading organisations so that they do not provide low pay, hazardous jobs, or excessive hours of work. Weeding out entrepreneurs who are either avoiders (with potential to grow, but decide to stay small to avoid the costs of compliance) or evaders (those non-compliant with healthy regulations) requires institutions of governance that can align the incentives of entrepreneurs with growth that enhances social value. Sometimes it is rent seeking officials who impose entry costs and regulations so as to create opportunities for corruption. At times it is misaligned policies and regulations that result in enterprises turning avoiders or evaders. In India faulty input price policies (such as low electricity tariffs for agriculture and domestic sectors, cross subsidised by industrial and commercial users; or the excessive costs of land acquisition due to holding out and rent seeking) for instance push business margins low and induce evasion.

It takes no less than an economy-wide crisis to bring out the social and economic costs of informality and the importance of formalisation. The scenes of migrant workers walking home on foot soon after the lockdown order is an indication that informality is double-edged. Those informal workers who migrate and send remittances provide a shock absorber and allow families to scrape through with a living. However, if their meagre income comes from casual employment, such as hawking roadside goods, then forced isolation will see them struggling to survive as the economy staggers to a standstill. Their living conditions too do not provide them with the means to stockpile food and social isolation is physically impossible. A lockdown over longer periods is only effective to the extent that an economy has testing capacity and responsive health systems. And in the intervening period it requires income support and functioning supply chains. Otherwise a lockdown is an unfair tax on the vast majority in the informal sector.

Persons who make their living in the informal sector have less scope for self-insurance by using part of their wealth as borrowing capacity to withstand income volatility. The litmus test for how policy makers handle the economic fallout of Covid-19 will be how much support can be provided to withstand the income shock. Formalisation of the economy supports policy in this endeavor as it provides for good risk sharing institutions. A good example is Switzerland’s package of emergency loans to small business unveiled on 25 March. The application was a one-page form and the money was credited into accounts within a day, enabling businesses to protect and pay their staff. Businesses could apply for an immediate interest free loan underwritten by the government worth up to 10 per cent of their annual revenue. The backbone to this was formal institutions – the scheme was run through the existing bank network as credit histories and customer relationships were leveraged. It was a fellowship of the political and business elite (cronies, to use the word in its positive sense) that got the programme quickly up and running.

The litmus test for how policy makers handle the economic fallout of Covid-19 will be how much support can be provided to withstand the income shock. Formalisation of the economy supports policy in this endeavor as it provides for good risk sharing institutions. A good example is Switzerland’s package of emergency loans to small business unveiled on 25 March. The application was a one-page form and the money was credited into accounts within a day

Cronyism as a word is much discredited today. But there is no getting away from the fact that unless policy makers (politicians and bureaucrats) and entrepreneurs are cronies in promoting and attributing high value to institutions of governance we will not see formalisation of the economy and the associated entrepreneurship that pursues growth opportunities instead of survival. The precarious circumstances in which large sections of the population live in the informal sector will only then be mitigated. Until then malfunctioning input and labour markets will exhaust the welfare State and families and produce dysfunctional inequality.

(Errol D’Souza is Director, IIM- Ahmedabad and Astha Agarwalla is Associate Professor at the Adani Institute of Infrastructure Management)