Much has been said and written during the last 12 months about the demonetisation of 2016. Some of these evince political bias or clear partisanship, while some others are in the genre of cheap hyperbole, especially those which attribute a rapine motive to the government. Again, one has seen a surge of penmanship and display of oratorical skills in the wake of its anniversary on November 8. A bit away in time from the din and dust caused by all this, one is perhaps in a better position to do an objective and dispassionate analysis of the effects of this momentous measure.

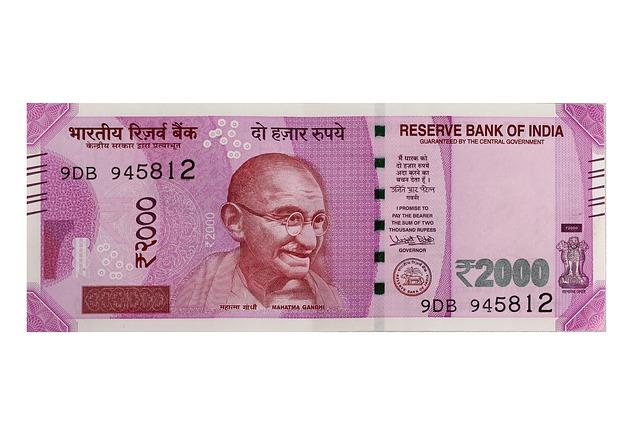

The objectives of this step, which even minutes before its announcement on November 8 evening would have seemed unthinkable to most Indians, as explained by the Prime Minister on that eventful evening were to make a decisive dent on corruption, black money, terrorism and counterfeit currency. They were subsequently expanded to include digitisation of payments and enlarging the number of tax payers.

It is now more or less clear that the proximate reason for the former RBI governor leaving his job without seeking a customary extension was his difference with the government over demonetisation: in his view, its significant short-term cost would outweigh its uncertain long-term benefits.

The most important expectation underlying the first set of objectives was that about a third of the demonetised notes valued at Rs.15.4 trillion and constituting 86.9% of the value of notes in circulation wouldn't be deposited. This seemed to be based on heuristic assumptions that about a quarter to third of high denomination notes in circulation represented undisclosed income and that funding of terrorism and illicit activities was almost entirely done in those notes. However, judged by this yardstick alone, demonetisation was not a success, as 99% of the demonetised notes were returned and there was no fiscal windfall to be showcased. But this in or by itself does not invalidate the underlying assumptions, although it will leave open the question whether demonetisation was the best way to deal with black money and corruption. Persons with previously undisclosed incomes who chose to deposit their cash in banks instead of destroying them were behaving perfectly rationally as they expected to salvage something from the tax net if caught.

How big was the transient pain?

It is now more or less clear that the proximate reason for the former RBI governor leaving his job without seeking a customary extension was his difference with the government over demonetisation: in his view, its significant short-term cost would outweigh its uncertain long-term benefits.

On the issue of short-term cost, the most obvious pointer has been the observed fall in the overall growth performance of the economy from the third quarter of 2016 onwards. Even one year later, there is a near-term loss of growth momentum as also a drop in consumer confidence. But the quintessential issue here is: to what extent can this be attributed to the demonetisation in a cause-and-effect sense? A few relevant quarterly growth numbers have been assembled in the accompanying table to examine this.

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | |||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | |

| Total | 7.2 | 6.6 | 5.6 | ||||||

| Agriculture | 2.4 | 2.3 | -2.1 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 6.9 | 5.2 | 2.3 |

| Industry | 7.7 | 9.2 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 9.0 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 1.5 |

| Services | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 7.8 |

Agriculture is a cash-intensive activity and it's obvious that the rabi season sowing and harvesting in 2016-17 was not affected by demonetisation. In fact,rabi food grain production grew 8.5% - the highest in the last 13 years. The fall in 2017-18 Q1 agriculture growth rate has been due to slowdown in allied activities. The signs of a slide in industry in 2016-17 and in Q1 of 2017-18 were evident at the beginning of 2016-17 itself with low and falling appetite for new investment 'as entrepreneurial energies flagged'. This was more likely because of the leveraged balance sheets of a good section of corporates and rising NPAs of banks than due to demonetisation. The effect of demonetisation was strong on the cash-intensive construction, financial, real estate and professional services within the services sector in Q3 and Q4 of 2016-17, although their rebound in Q1 of 2017-18 was strong. Overall, one can surmised that the fall in growth performance of the Indian economy in 2016-17 and thereafter cannot be attributed to demonetisation alone and there are other forces at work in this regard. We need good quality research to reveal the facts here. However, this conclusion is not to belittle the disproportionate hardship that low-income families, particularly those in the informal sector, had to go through at least for few weeks because of the dislocation caused to their lives and livelihoods.

Among the several possible long-term benefits of demonetisation, the following three are worth mentioning, since there are incipient signs that they are gaining hold:

(a) A culture of better tax compliance.

(b) Expansion of the envelope of formal financial sector

(c) A payment system which is less reliant on cash transactions

A narrow direct-tax base, a retrograde direct-indirect tax structure, widespread tax evasion, complex tax rules, an inefficient and rent-seeking tax administration have been the hallmark of Indian taxation system since independence. Its dysfunctional nature has shaped the incentives of politicians, bureaucrats, businessmen and tax-payers, in general, in a way that engendered corruption and black money. A recent survey conducted by Transparency International in 16 Asia-Pacific countries revealed that India had the highest bribery rate among them. This comes as no surprise, but what is encouraging is that over a half of the respondents from India were positive about the government's efforts to combat corruption. To expand the ambit of discussion to include tax evasion and corruption in the context of demonetisation does not mean any shifting of the goal post. Also, it hardly matters even if the government's post-demonetisation drive on tax evasion is an after-thought, since it seems to be yielding some results never seen before: the number of income-tax filings increased significantly this year, use of cash in real estate deals has come down and the tax-men are now making diligent efforts to uncover cases of tax evasion based on the information of large cash deposits made during demonetisation. For the first time again, the age-old practice of forming shell companies for tax evasion and other unlawful activities now faces a serious challenge from the authorities. Overall, there is anecdotal evidence to infer that the environment for tax compliance is improving.

Demonetisation led to a notable increase in financial intermediation with 48% increase in deposits in Jan Dhan bank accounts. Further, 38.2 million new accounts were opened post-demonetisation till end-July this year. This is certainly a big boost for financial inclusion.

For India, where more than 95% of retail transactions were in cash before demonetisation, any policy goal and action to reduce use of cash and aggregate holding of cash are welcome. A year after demonetisation, currency in circulation is about 10% less than its pre-demonetisation level and 19% lower vis-a-vis what would have been the level now sans demonetisation.

Digital transactions – both P2P and merchant varieties – are on the rise. October, 2017 saw the highest ever transaction volume at 965 million, exceeding the previous high of 957.5 million in December, 2016. RBI may be just right in observing in its last annual report that 'There appears to be a structural break in the volume and value of retail electronic payments, coinciding with...demonetisation'. This augurs well for the country.

(The writer is a former central banker and consultant to the IMF)