The Indian economy is at the crossroads, grappling as it is now with a massive slowdown and escalating inflation. The endeavour of the authorities to counter this challenge has fallen short. It appears that a situation of policy helplessness has emerged. The current slippage is nothing short of shocking and the zeal with which quick fixes are being discussed might suggest that the game is already lost. That cannot be a place to have conversations on policy.

The headline inflation rate (measured in terms of Consumer Price Index Combined, (CPI-C), which is the official measure of the inflation target, was placed at 7.35 per cent in December 2019. At this level, the inflation rate has been much above the ceiling of the targeted 6 per cent. It may be noted that the inflation rate at 5.54 per cent in November 2019 was higher than the target average rate of 4 per cent and very close to the ceiling rate. The composition of the retail inflation rate reveals that the high rate has been contributed to by food inflation, which was as high as 12.16 per cent due to higher vegetable inflation (60.50 per cent) and pulses inflation (15 44 per cent). Fuel inflation, comprising fuel and light and transport and communication, has been lower at 0.70 per cent and 4.77 per cent.

The inflation outlook (5.1 to 4.7 per cent for H2 of 2019-20 and 4.0 to 3.8 per cent for H1 of 2020-21) has been far less than the December 2019 actual inflation (7.35 percent). Needless to say, such a high inflation rate with a large food inflation component is an enormous burden on the common man. Besides, a much higher actual inflation rate than that of the projected rate by the RBI has raised new doubts on the integrity of inflation forecasting by the RBI, which is the intermediate target of the current monetary policy framework.

In the above context, two observations are important. First, even though the headline inflation is higher, the core inflation (defined as headline inflation minus food and fuel inflation), which measures the persistence of inflation, is lower at 3.75 per cent. But it may be noted that the mandate of inflation management rests on headline and not core inflation. Therefore, the onus of monetary policy is to reduce the headline inflation rate to an average of 4 per cent. Second, the inflation outlook (5.1 to 4.7 per cent for H2 of 2019-20 and 4.0 to 3.8 per cent for H1 of 2020-21) set out in the fifth bi-monthly Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) resolution has been far less than the December 2019 actual inflation (7.35 percent). Needless to say, such a high inflation rate with a large food inflation component is an enormous burden on the common man. Besides, a much higher actual inflation rate than that of the projected rate by the RBI as mentioned above has raised new doubts on the integrity of inflation forecasting by the RBI, which is the intermediate target of the current monetary policy framework.

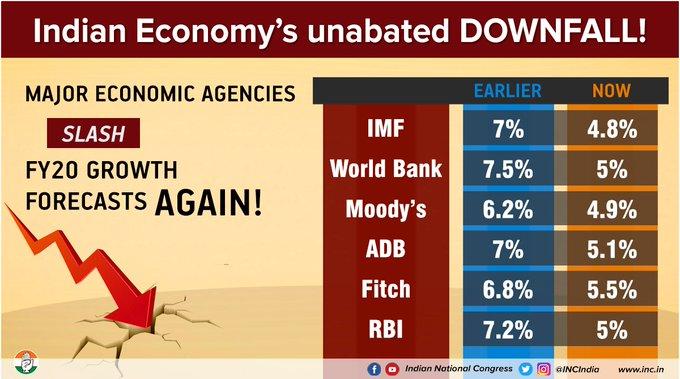

The rate of economic growth measured in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from the demand side (expenditure method) and Gross Value Added from the supply side (economic activity in Agriculture, Industry and Services) for 2019-20 as released by the government stood at 5 per cent and 4.9 per cent respectively on a y-o-y basis. It may be noted that the projection of 5 per cent GDP growth is the same as the RBI’s projection. For H1 of 2020-21, RBI has projected a GDP growth rate of 5.9 to 6.3 per cent. The data on Index of Industrial production (IIP) for April – November 2019 revealed that mining, manufacturing and electricity, three critical sectors, have shown lower growth. Besides, key manufacturing groups such as electrical equipment, paper and paper products, machinery motor vehicles and petroleum products, have witnessed negative growth. Capital goods and infrastructure recorded a negative growth of 11.6 per cent and 2.7 per cent respectively in the same period.

Though strictly not a stagflation scenario, the Indian economy has thus entered a dangerous zone of slump in economic growth accompanied by intensifying retail inflation – a heavy encumbrance on the poor. What could be policy actions? If we go by the spirit of the December 05 MPC resolution coupled with the November and December 2019 higher retail inflation print, even though the monetary policy will remain accommodative, the scope of further rate cut is nearly absent. If inflation print does not recede, the stance could be shifted from accommodative to neutral. In a slowdown phase, any increase in policy repo rate is ruled out. The escalating food inflation is eating off the lion’s share of family/ household budget so there is less scope to revive the durable consumption. Reflecting this, consumer durables witnessed a negative growth of 6.5 per cent in April- November 2019.

There are structural rigidities in terms of disintermediation of savings from the financial side to physical side such as gold and real estate. Persistence of a huge revenue deficit is a perennial impediment to government savings and thus to the overall savings rate. Elimination of the revenue deficit is an answer to boost savings and create headroom for investment by the government. Foreign Direct Investment needs to be encouraged to supplement the domestic investment.

Since there is less scope and space in the monetary policy to revive growth, as explained above, there are emerging views to revive growth through fiscal stimulus, by defaulting on the FRBM fiscal deficit target. It may be noted that fiscal policy may be geared up to enhance disposable income by reduction in tax; some action has been made by the government to reduce corporation tax and the ensuing union budget may have a proposal to reduce personal income tax. On the expenditure front, government consumption expenditure may be enhanced in the areas of subsidies, rural development and MNERAGA to boost government and private consumption. But such a manner of growth revival has a huge cost to the economy in terms of a vicious cycle of deficit and debt, thereby placing an adverse impact on public debt management and monetary management.

What is important in the above context is to recognise that the aggregate demand management by the authorities by means of interest rate reduction (monetary policy interventions), fiscal stimulus through consumption expenditure enhancement and/or tax reduction (fiscal policy intervention), will both have limited success to move to a trajectory of non- inflationary sustainable level of growth. There are structural rigidities in terms of disintermediation of savings from the financial side to physical side such as gold and real estate. Persistence of a huge revenue deficit is a perennial impediment to government savings and thus to the overall savings rate.

Elimination of the revenue deficit is an answer to boost savings and create headroom for investment by the government. Foreign Direct Investment needs to be encouraged to supplement the domestic investment. There are no quick fixes to address the challenges of growth and inflation. What we need is a commitment to structural reforms, with single- minded focus and devotion if we are to move to a non- inflationary growth trajectory that is sustainable over the medium and long term. There may be a debate on what those reforms must be, and how they must be prioritised. Unfortunately, what we have today is a talk of unattainable quick fixes that may (or may not) give temporary relief while the root cause of the ailment remains untreated.

(The writer is a former central banker and a faculty member at SPJIMR. Views are personal)