At a function held at the Taj Mahal hotel almost three decades ago, the renowned telecom engineer, inventor, entrepreneur, policy maker Sam Pitroda spoke of what technology could do. He said watermelons could be grown square in shape so that they could be packed better and transported with ease. The Shiv Sena chief, the late Bal Thackeray, who was at the function, was intrigued and later remarked he was more concerned about the state of public toilets and how people were easing themselves on the streets.

Both were right but they presented different perspectives on what they thought were the problems of the nation and the city; they reflected a different worldview. Thackeray, a Mumbaikar, spoke of what he saw as a huge problem in the city (and the State) that his party would go on to govern as the Shiv Sena rose to power. Pitroda, a tech wizard, spoke of what could be if only we could put our heads together and worked towards it.

The index is constructed for 157 countries, of which India is one but sits not too well, at rank 115, lower than many of its neighbours. Singapore tops the list. The US is at the 24th rank. The Indian government has been quick to announce that it will “reject” the HCI, citing “serious reservations about the advisability and utility of this exercise…there are major methodological weaknesses, besides substantial data gaps.”

Pitroda went on to help drive India’s telecom revolution and build the physical infrastructure that has helped connect remote parts of the nation and drive new areas of growth. The Shiv Sena chief on the other hand was talking of a focus that could build health and sanitation – areas that could drive human capital. The two together is what gives growth that is sustainable and meaningful for a wide majority of the people.

India at 115 in HCI

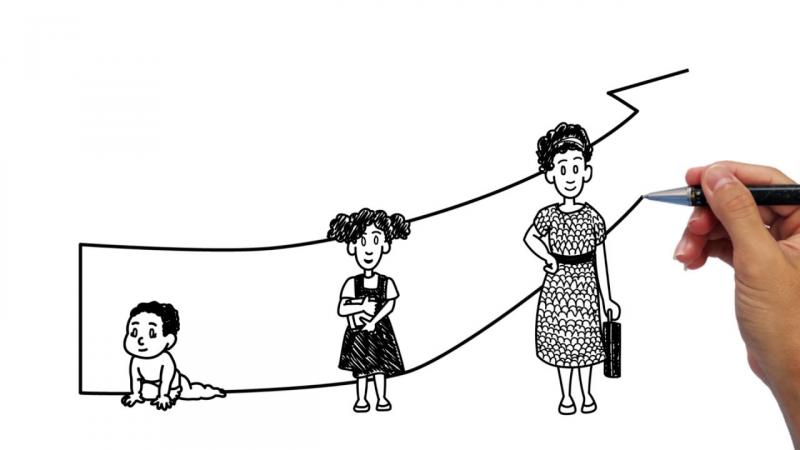

The two, physical capital and human capital, are in focus today following the release by the World Bank of the Human Capital Index, or HCI. The HCI is a new index that measures the amount of human capital that a child born today can expect to attain by age 18. It conveys the productivity of the next generation of workers compared to a benchmark of complete education and full health. The index is constructed for 157 countries, of which India is one but sits not too well, at rank 115, lower than many of its neighbours. Singapore tops the list. The US is at the 24th rank. The Indian government has been quick to announce that it will “reject” the HCI, citing “serious reservations about the advisability and utility of this exercise…there are major methodological weaknesses, besides substantial data gaps.”

HCI is made up of five indicators: the probability of survival to age five, a child’s expected years of schooling, harmonised test scores as a measure of quality of learning, adult survival rate (fraction of 15-year olds that will survive to age 60), and the proportion of children who are not stunted.

That India, as the world’s fastest growing economy, can sit so low on human capital is in many ways an eye-opener. It summarises in one number what is seen, felt and experienced by citizens on a day-to-day basis in two key areas that drive growth: health and education.

india’s HCI stands at 0.44, which means a child born in India today will be 44 per cent as productive as she could be if she enjoyed complete education and full health. This is a number lower than that of Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar, and raises some questions on the manner and direction of our efforts at driving inclusive growth. In 2017, India’s HCI stood lower than the average for its region and income group. That India, as the world’s fastest growing economy, can sit so low on human capital is in many ways an eye-opener. It summarises in one number what is seen, felt and experienced by citizens on a day-to-day basis in two key areas that drive growth: health and education.

The reality of India today is that we have high quality hospitals that treat specialist diseases and run expensive cosmetology centres for elective surgeries offered to the elite while cases of malaria and dengue can drain the ordinary citizens of savings as healthcare costs shoot up. Schooling is increasingly expensive as fancy buildings with air-conditioned classrooms mushroom, many of them offering international curricula while primary schools in the public sector languish.

The poor showing in the HCI comes up because the Index seeks to study not just the investments but also looks at outcomes. For an example, in India, in terms of probability of survival to age five, we have that 96 out of 100 children born in India survive to age five. But 38 out of 100 children are stunted, and so at risk of cognitive and physical limitations that can last a lifetime. In India, a child who starts school at age four can expect to complete 10.2 years of school by her 18th birthday but factoring in what children actually learn, expected years of school is only 5.8 years. Considering harmonised test scores, students in India score 355 on a scale varying from a high of 625 to a low of 300. So what works on paper or certificates is not what we get.

The government has noted that the purpose of the Index is to create political incentive for increased spending on health and education. “But the indicators used for measuring the Index are so slow moving that none can really be excited about setting out the programme of Index improvement. Adult survival rates, stunting, and under five mortality are outcome indicators will change at a relatively slow rate as compared to process indicators used in computing, for example, the Ease of Doing Business,” the government argued in a statement issued the very day the HCI was released.

“Slow moving indicators” that do not bring any excitement to policy makers is in many ways a significant aspect of the problem. Some key areas of change are slow to drive but must nevertheless be driven irrespective of whether they show up on the charts, bring in the votes or move indices that work like a seal of approval for governments around the world.

A global movement that focuses on human capital as a driver of change and growth for a new generation is a welcome move. It turns focus from physical infrastructure, a “here and now” issue and therefore more looked at, to human capital, which will yield dividends much later, and can help change conversations and policies to improve and drive long term growth and carry people who are often excluded.

A global movement that focuses on human capital as a driver of change and growth for a new generation is a welcome move. It turns focus from physical infrastructure, a “here and now” issue and therefore more looked at, to human capital, which will yield dividends much later, and can help change conversations and policies to improve and drive long term growth and carry people who are often excluded.

One in four kids undernourished

Consider the global situation presented in an “open letter to the world” signed by a group of global leaders that included the President of the World Economic Forum, Børge Brende, CEO of Philips Frans van Houten, Executive Director of UNICEF Henrietta Fore, President of The Rockefeller Foundation Dr. Rajiv. J. Shah and President of the World Bank Group Dr. Jim Yong Kim.

- More than half the world’s population cannot access essential health services, with almost 100 million people pushed into extreme poverty every year by health costs.

- In the world’s poorest countries, four out of five poor people are not covered by a social safety net, leaving them extremely vulnerable.

- An estimated 5.4 million children under 5 years of age died in 2017, mostly of preventable causes. Newborns account for around half of those deaths.

- Over 750 million adults are illiterate, their lifetime productivity severely diminished by a poor education.

- More than 260 million children are not in primary or secondary school. And another quarter of a billion children cannot read or write despite having gone to school. If they formed a country, it would be the third largest country in the world.

- Nearly one in four young children around the world are undernourished (stunted), their life prospects permanently limited by an accumulation of adversity in their earliest years.

That is how the World Bank has framed the urgency of human capital. It launches a case for nations to build human capital today to secure the future tomorrow. That India rejects the HCI is unfortunate.