There was great uncertainty in 1999 about the outcome of India’s national election and concern that India’s development would be disabled by India’s competitive politics. The dominance of a single party, the Congress, in national and State politics was fading then. Regional parties had gathered strength. The decade following the landmark reforms of 1991 had seen many coalition governments cobble together at the centre and collapse, some within months. There was fear that without a strong centre India’s development story would fall apart. While, on one hand, hoping that a single party and a strong central leader may emerge because it would provide stability in governance, there was then, as there is now, the fear of the harm an autocracy might inflict on India’s democracy. (The memory of the Emergency was vivid).

We may confidently predict, however, that for some more decades Indian politics will be in churn while its social and economic structures are reformed. A corollary of competitive politics, along with the churn, will be high levels of corruption, which is hard to eliminate even in stable societies, and much harder in changing societies.

Scenarios were prepared in 2000, using systems thinking, to project what the shape of India’s economy and democracy would be under different forms of government—strong single party, or potentially unstable coalitions. These scenarios were summarised in a report, Scenarios for India 2010: An Invitation to Make a Difference. They also analysed which institutions must be strengthened to de-risk the Indian economy from political instability. Scenarios are not predictions. They are projections of plausible outcomes. Scenarios help to develop strategies that will make the enterprise successful in all plausible scenarios.

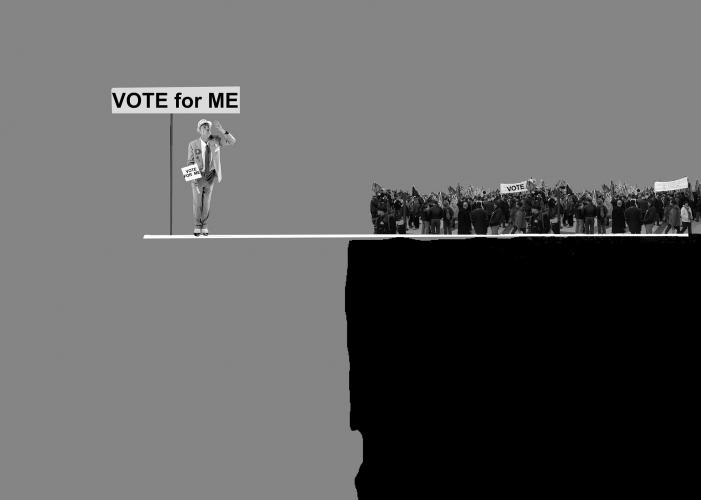

Four alternative outcomes of future elections were envisaged in 2000. The same four can be envisaged even now. They were described in broad brush terms:

A. Kaleidoscope. In this configuration power in the Centre and in the States is shared by several parties. The quality of the political configuration could be either:

A1. Federal Harmony (The parties respect each other and learn to work together), or

A2. You stab my back I stab yours (“Politicians provide front page entertainment”)

B. Monochrome. In this configuration one party dominates throughout the country. The quality of the governance could be either:

B1. Ramrajya (Magnanimous enlightened leadership, with losers cooperating in the nation-building agenda), or

B2. Volcano (Seething trouble, with losers waiting to strike)

The outcome of the national elections in 2019 is unpredictable. It could be any of the four configurations described. We may confidently predict, however, that for some more decades Indian politics will be in churn while its social and economic structures are reformed. A corollary of competitive politics, along with the churn, will be high levels of corruption, which is hard to eliminate even in stable societies, and much harder in changing societies. Indeed, as Samuel Huntington suggests, in Political Order in Changing Societies, the proceeds of corruption can bind together otherwise unstable social groups. This has been observed in India, in the politics of UP, Bihar, and Tamil Nadu, where the acquisition of power by historically suppressed communities as well as corruption grew at the same time.

Power must be devolved down to local levels. People should be able to govern their own lives more directly for the democratic ideal of ‘government of the people, for the people, by the people’, to become a reality. The need for ‘lateralisation’ of governance with more effective collaboration amongst various stakeholders is required too. The third ‘L’ is an emphasis on the system’s ability to learn, rather than on the design of systems for top down monitoring and control.

The question for scenarists in 2000 was: what institutional structures will stabilise India’s economy and society even when competitive politics churns governance at the top. Their systems analysis described the institutional architecture India needs: a vast, diverse, and democratic country that aspirates for faster growth. The institutional architecture is founded on four ‘Ls’—Localisation, Lateralisation, Learning, and Listening.

Power must be devolved down to local levels. People should be able to govern their own lives more directly for the democratic ideal of ‘government of the people, for the people, by the people’, to become a reality. The need for ‘lateralisation’ of governance with more effective collaboration amongst various stakeholders is required too. The third ‘L’ is an emphasis on the system’s ability to learn, rather than on the design of systems for top down monitoring and control. The need to shift decision-making power in development programs downwards had become clear in the last term of the UPA government. In 2014 the NDA government abolished the Planning Commission, with the intention of promoting a competitive-cum-collaborative federalism, and learning across the States, facilitated by a new institution, the NITI Aayog.

The fourth ‘L’, better listening, is critical for dialogues that build lateral collaborations and for faster learning. Above all, it is essential for social harmony. Alas, with the spread of social media, and with even political leaders tweeting about each other, rather than talking to each other, no one seems to be listening to others’ points-of-view.

An enduring image that emerged from the scenario analysis is an image of ‘Fireflies Arising’. Many small initiatives and innovations that spring up in greater abundance, each bringing its own light, and connecting together in a rising swarm of change, can turn darkness into light. This scenario will be produced by strengthening the capacity of local institutions, urban and rural, and by facilitating clusters of small enterprises around the country. This scenario is a projection of what India must aspire to be: a democratic country advancing, economically and socially, democratically, not autocratically.

It is time to write a new story of India in which communities of diverse people, respecting each other, and supporting each other, are the principal agents for making the world better for everyone. The most effective ‘big ticket’ reform that India’s leaders can make is to strengthen governance by the people in its cities and villages.

The scenarists projected the condition of the country in all political configurations if the institutional strategy that leads to the Fireflies Arising scenario was pursued. They also examined likely condition if this strategy was not followed. The unambiguous conclusion was that the country would be ‘de-risked’ against electoral uncertainties if the base of governance was strengthened with the 4 L strategy. What was foreseen in 2000, can be projected in 2018 too, looking at India’s development beyond the 2019 elections.

It is time to write a new story of India in which communities of diverse people, respecting each other, and supporting each other, are the principal agents for making the world better for everyone. The most effective ‘big ticket’ reform that India’s leaders can make is to strengthen governance by the people in its cities and villages. Our constitution requires it. It will strengthen India’s democracy, its economy, and its society.

(The writer is a former member of the Planning Commission and author of the recently released book “Listening For Well-Being: Conversations with People Not Like Us”)