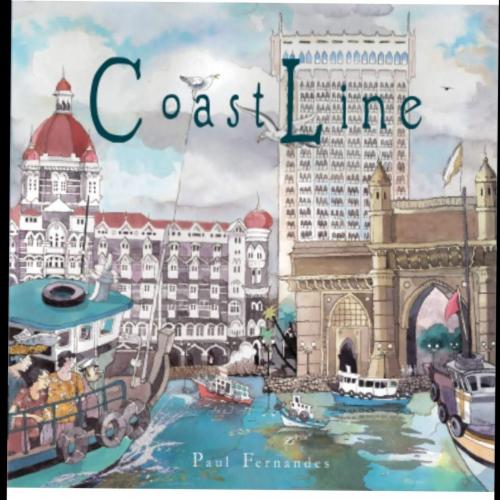

It turned out to be a discussion on the city of Mumbai. The venue was the Taj Mahal hotel and the occasion was the launch of a big fat book called ‘CoastLine’ that tells the tale of Mumbai and the larger Indian coastline in caricatures and charming stories by the uniquely talented Paul Fernandes, the Bangalorewallah who never forgot his brief stint in Mumbai. Fernandes is as quiet and understated as his drawings are bold, colourful, flavourful – Mario-esque but unique in the way they can jump out of the pages and tell the story of Mumbai and the Indian coastline. Fernandes covers all of the vast Indian coastline in his book but sitting in the Gateway Room of the Taj Mahal hotel, overlooking the Gateway of India, with former Congress MP Milind Deora on stage next to Gerson daCunha, the subject naturally veered to Mumbai and the state of the city.

Gerson daCunha’s lament, given what the city is going through, is significant in that it comes at a time when Mumbai is seized by a new push – developmental for some but destructive in the ways it excludes, diminishes and marginalises the ordinary citizen who is the lifeblood of the city.

DaCunha’s lament

Naresh Fernandes, the unassuming editor of Scroll, asked daCunha, journalist, ad guru, author, actor and activist, what were his thoughts on Mumbai as he looked out of his home to the Oval maidan.

“Well,” replied daCunha, who is 89, “I lament the decline of the city because I remember a Bombay where the streets used to be washed with chlorinated water every day. There was a van and behind that van, like a bridal veil, was a shower of water that washed the roads. Today, if you think of 10,000 metric tonnes of garbage that go every day to the dump sites…the memories you have are heart wrenching but then one does not lose hope because of the people of the city…”

It is of course true that people define the city and are in turn defined by it. In fact, the fortunes of Mumbai have been compared to that of an “extremely poverty-stricken man who, either by the dint of his efforts or with the help of a rich man, achieves a state of prosperity.” The words come from the 1863 account of Mumbai by the journalist Govind Narayan (Mumbaiche Varnan in Marathi, translated by Murli Ranganathan). In that sense, the story of Mumbai is precisely the story of its citizens – harried, rushed, pressured but still out to make their mark in their own way.

It is of course not uncommon to see almost every generation look back longingly to snatches from the past – it is not what it used to be! Govind Narayan’s Mumbaiche Varnan had a hint of it (“There were no sprawling mansions and bungalows, which are common now. Instead of glass, the window panes were made from sea-shells”) and daChunha sees it now. Yet, daCunha’s lament, given what the city is going through, is significant in that it comes at a time when Mumbai is seized by a new push – developmental for some but destructive in the ways it excludes, diminishes and marginalises the ordinary citizen who is the lifeblood of the city.

The city is the story of fancy international schools as everyday schools, particularly municipal schools, are allowed to slide, or have already been killed. Small neighbourhood nursing homes make way for “specialty” hospitals with a range of facilities – the birth cradle of a new system that brought for all of us escalating costs and medical care that is poorer and shoddier and heartless in the way it dehumanises the poor and the weak.

Development or destruction

So it is that we have a Trump Tower coming up, and many other high rises that pockmark the skyline with concrete facades, ugly unfinished monuments that stand testimony to a sector that is in decline as investors run away from the real estate market and real buyers are nowhere to be found. Meanwhile, as daCunha pointed out, two-thirds of the city lives in the slums. The city bus service, the BEST, long held as the transport that Mumbai can truly be proud of, is being slowly killed – a long strike by transport workers has just ended but the agreements provide no guarantee that the service will be given the support and the nurturing it requires to ferry the ordinary folk around.

The T2 is a fancy terminal, standing up to international standards with its own flyover, but the roads away from that fancy spot are as poor as they were, or worse. The railway stations used by many more – the Bandra terminus, the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus and others – show no signs of improving services. At the airport itself, the system works with privileged parking for privileged prices – those taking ordinary taxis must walk further, those in autos must walk even more, those taking buses…that’s made more difficult and almost no one takes a bus. That’s how the terminal is designed. Crisscrossing metro lines are the new buzz. They are, at last, on the way but there is little understanding of how affordable they can be for the ordinary citizen.

As the author, Fernandes puts its rather well: “The people I see are hard-working, fun loving and caring. I was fascinated by everything about them: the way they live their lives, their choice of food and drink, their pastimes and passions…all of which, of course, are the natural and charming offshoot of the seaside world they call their home.”

The city is the story of fancy international schools as everyday schools, particularly municipal schools, are allowed to slide, or have already been killed. Small neighbourhood nursing homes make way for “specialty” hospitals with a range of facilities – the birth cradle of a new system that brought for all of us escalating costs and medical care that is poorer and shoddier and heartless in the way it dehumanises the poor and the weak.

No more protests

At the same time, protests have by and large disappeared. The voices that used to rise, to alert, to vent off, to bargain, to make a counterpoint seem silenced amid this march of development so that we can see a frenzy of activity and think we are marching ahead. Yet, this may be a march to doom because the city is nothing without its ordinary people – they run the hospitals, the hotels and the taxis, the autos and the services. They sweep the floors and the streets, even if not with chlorinated water anymore. If the voice of the ordinary people dies, the city dies.

Coastline takes a sunnier view. It is colourful, full of life and is full of people. That’s what it celebrates, and in that it is truly a book that captures the spirit of Mumbai with people at the centre. As the author, Fernandes puts its rather well: “The people I see are hard-working, fun loving and caring. I was fascinated by everything about them: the way they live their lives, their choice of food and drink, their pastimes and passions…all of which, of course, are the natural and charming offshoot of the seaside world they call their home.”

(The author is a journalist and a faculty member at SPJIMR. Views are personal)